This article was written by one of our staff instructors and originally appeared on the SDI website.

It’s been a long and relaxing dive. You and your buddies have gone from one coral head to another. You snap photos and marvel at the aquatic life. The catch is, your pressure gauges say it’s time to head back to the boat. Unfortunately, you’ve lost track of where you are.

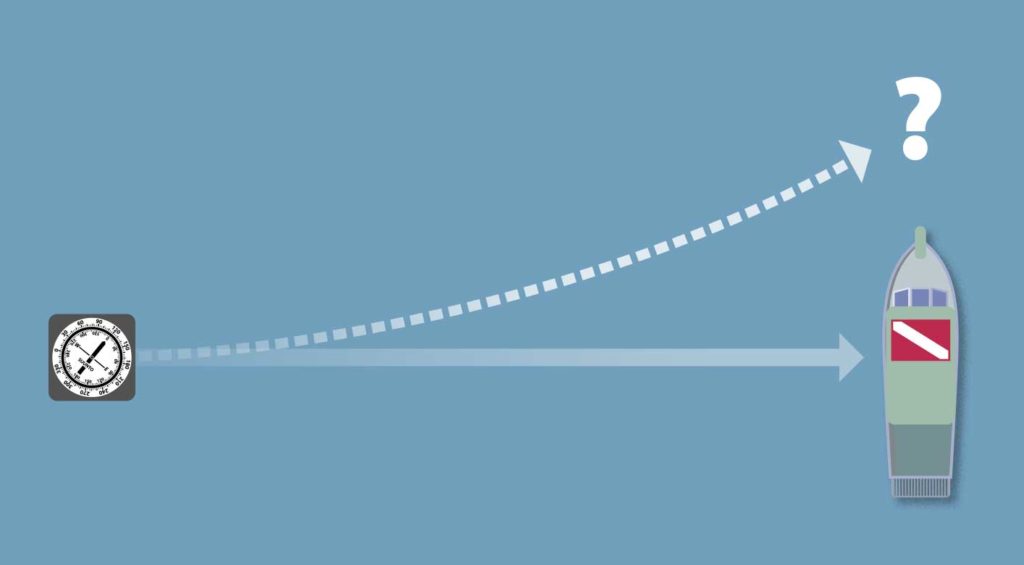

The good news is, you are in very shallow water. Coming to the surface to take a compass heading on the boat won’t create the problems usually associated with bounce dives and sawtooth profiles. You surface and see the boat approximately 100 m/330 ft away. You take a heading on the boat so you can return on the bottom.

You and your teammates could swim back on the surface. But you remember your instructor telling you to avoid long surface swims when possible. Underwater, you avoid waves, strong surface currents, and boat traffic. You have plenty of air left, so returning to the boat underwater seems like the best option.

With your buddies in tow, you align the centerline of your compass with the centerline of your body and swim at a relaxed pace. You remember from your Advanced course you can expect to cover roughly 25 m/80 ft per minute at this pace. Your relaxed pace should get you back to the boat in four minutes.

Four minutes pass. You look up. No boat. Not even the shadow of the boat on the bottom.

You and your teammates surface. Looking around, you spot the boat 20 m/65 ft away. You elect to swim the rest of the way on the surface.

You’re frustrated, though. All the way back, you kept your eyes glued to the compass dial. You did your best to keep your body aligned with the compass’s centerline. What went wrong? And what can you do to prevent this from happening in the future?

Compass use has limits

Underwater compasses work best over short distances. Why? Because no matter how carefully you try to keep your body aligned with the compass, you can still be off by more than 10 to 15 degrees. Several factors can affect this.

- Despite your best efforts, the centerline of your compass may not be perfectly aligned with your body. This is especially true when using wrist-mounted compasses or compasses built into wrist-mounted computers.

- A current coming from either side of your direction of travel can easily push you off course.

- Most of us have a leg which is slightly stronger than the other. You tend not to notice this when kicking, but your dominant leg can push you off course in the opposite direction.

As the earlier example shows, over the length of a soccer or football field, these factors can cause you to miss your target by more than the length of a dive boat.

So what can you do?

There are several steps you can take to improve compass course accuracy.

- Keep compass legs short: If you must travel a long distance in shallow water, consider surfacing partway through to double-check your heading.

- Use a frog kick: It is less likely to affect your course if one leg is stronger than the other.

- Allow for current: If you detect a cross current, alter your course slightly in the direction from which the current is coming.

This may be the best trick

If swimming in poor visibility or over a featureless bottom, you may have no choice but to keep your eyes glued to the compass and hope for the best. But if you have even modest visibility, there is a trick that can dramatically improve your compass course accuracy. Here is how it works:

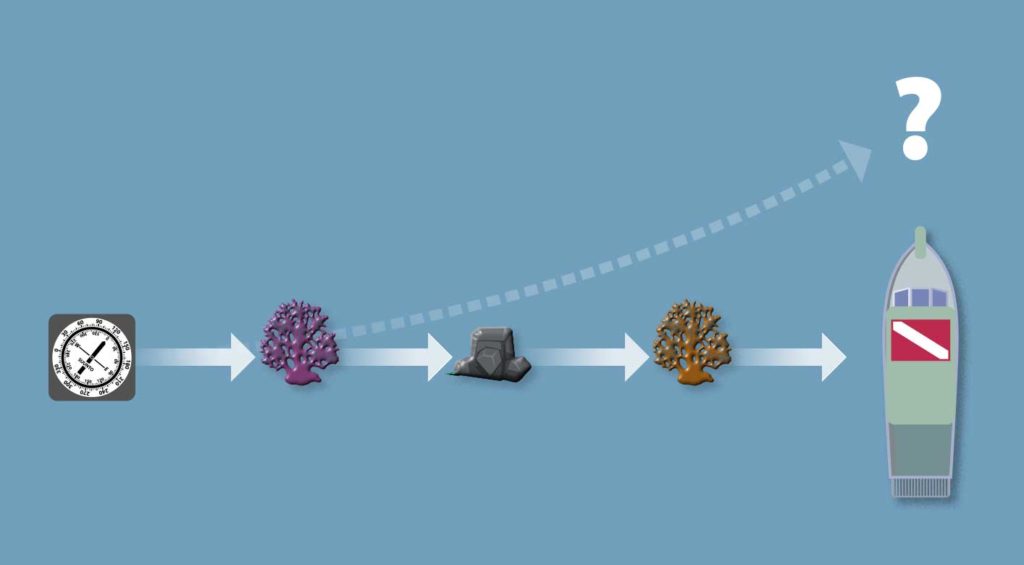

- Start by pointing your compass in the right direction. In other words, the heading you set on the surface.

- Sight down the centerline of the compass. See if it is pointing directly at an object in the distance. It can be a rock formation, a coral head, vegetation or a man-made item. It doesn’t matter.

- If it is, put the compass down and swim to the object. If it is pointing slightly to the right or left of an object, swim to that point.

- When you reach the object, use the compass to identify yet another distant object and swim to it.

- If there are no objects in your line of travel, follow the compass as you normally would until you see an object in your path. Then swim to it.

Repeat this process until you arrive at your destination.

Because the objects to which you are swimming can’t move, you can achieve close to 100 percent accuracy. It’s also a lot more fun than having your eyes constantly glued to the compass dial.

Things to remember

Compasses can help you in several ways.

- If you know the correct heading, they can help you find a wreck or other dive site when entering from shore.

- They can help you take a shortcut across a body of water rather than having to swim all the way around the edge.

- As you read at the beginning of this article, if you lose your bearings in shallow water, surfacing to take a compass heading on the boat or exit point can allow you to return underwater.

Preventing problems, however, is better than having to solve them.

- Make sure you always know where you are underwater. Don’t just wander aimlessly.

- Remember also surfacing to take a compass heading on your exit point may only be a viable option if diving in shallow water, typically 6-10 m/20-30 ft or less. If deeper than this, you do not want to be bouncing up and down like a yoyo.

- If using a dive charter, remember the captain probably went to great lengths to park over the best underwater scenery. You’ll see the most by sticking close to the boat.

Your Open Water Diver course covered only the most basic facets of underwater navigation.

- You can learn more about finding your way underwater by taking the The Dive Source Advanced Diver course.

- You can further expand on this by following the Advanced course with the Underwater Navigation Specialty Diver course. — © 2120-2121, Sinulogic LLC